The Reggae Philosopher

The versatile virtuoso Horace Andy describes his life in music to David Katz, from riffing with Bob Marley to fronting Massive Attack

By David Katz

February 14 2023

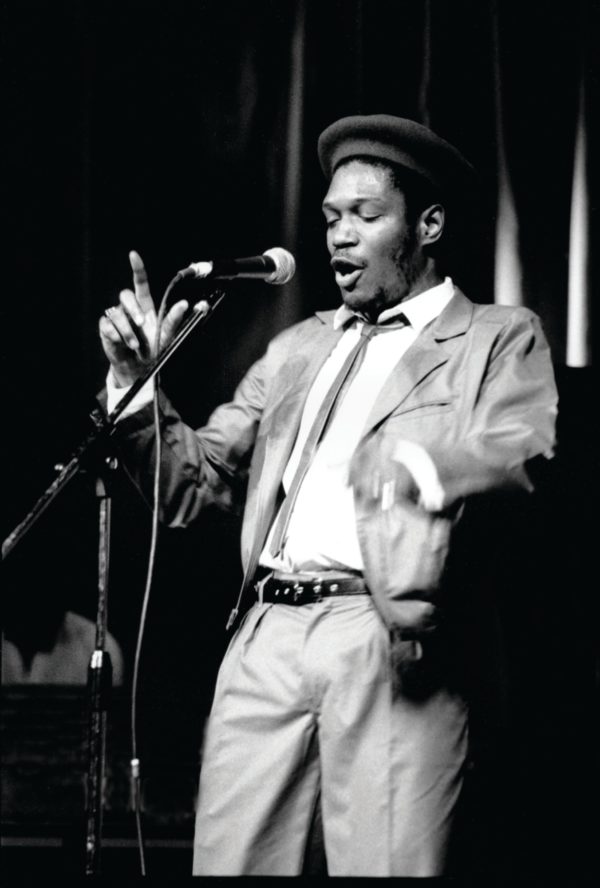

Best known in his native Jamaica for shimmering odes to religious faith and hard-hitting songs of social commentary and delivered in a quavering alto, Horace Andy is a reggae veteran of uncommon versatility. The public voice of Massive Attack for the last thirty years, he has collaborated with everyone from The Clash’s Joe Strummer to House music producer Ashley Beedle, though British audiences first got hooked on his reggae love ballads and unusual cover tunes, including a gritty rendition of Tom Jones’ ‘Delilah’, evidencing the range of influences brought to bear in his formative years.

“When I was young, I would sing any song,” Horace explains, on the other end of a crackling phone line in Jamaica. “I used to sing Otis Redding in the evening times, like (‘Sittin’ on) ‘The Dock of the Bay’, but before I started singing, I wanted to be Jimi Hendrix, because I was learning to play the guitar and his style really appealed to me. Tom Jones was always one of my big, big idols, and then Mick Jagger is one of my favourites, because The Rolling Stones ‘Angie’ was very popular in Jamaica. I love it and I played it so much, just like ‘Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree’ by Tony Orlando and Dawn.”

If crooner-producer Tony Orlando seems an odd role model for the man who recorded some of reggae’s deepest roots anthems, it makes sense that Horace would be drawn to diverse forms, since the culture of the sound system was all around him during his youth in the ghettos of western Kingston, exposing him to rhythm and blues, country and western, soul, rock, and pop, along with the indigenous folk style called mento and pan-Caribbean genres such as calypso and rumba. Music was simply part of everyday life from day one, so Horace discovered he could sing while still in short pants. “I think I was born with it in me, and I was already singing nursery rhymes in the classroom,” Horace reminisces.

During his teens, he made his debut recording, ‘Black Man’s Country’, for an upcoming producer called Phil Pratt, but the song made little impact, leading Horace to hone his musical skills for the next few years. “I couldn’t really sing then, so I had to learn to play the guitar and to sing properly,” he says with a chuckle. “Then I decided to go to Studio One, and I say Studio One was high school, college and university, ’cos that’s where I learned everything.”

Often likened to Jamaica’s Motown, Studio One was the island’s premier recording facility and group of record labels, where Horace’s friends Bob Marley, Ken Boothe and countless others got their start. Once he began recording there, the popularity of dejected-love

songs ‘Got to be Sure’ and ‘Love of a Woman’ brought Horace onto prominent stage shows in Kingston, including a stadium gig at the National Arena in 1971. Then, Horace Andy became an island-wide household name when his caustic ‘Skylarking’ topped the Jamaican charts; a song decrying the lack of employment opportunities for local youth, demonstrating his social and spiritual awakening.

“Being a young male Rastafarian, looking at what’s happening, that’s why I sing that song,” Horace explains. “Living as a Rastafarian, you’re going to be doing political songs all the time.”

He followed ‘Skylarking’ with the devotional ‘Children of Israel’, another Number One hit, and heartfelt love song ‘You Are My Angel’ became the title track of a popular 1973 album released by Trojan Records, based in Brent in London, widening Horace’s audience overseas before RCA issued some songs he recorded with Bob Marley’s backing musicians, the releases all forming stepping stones to international success.

Seeking to widen his horizons, Horace moved to the United States during the late Seventies, settling first in Brooklyn and later in Hartford, Connecticut. His time on the East Coast inspired a musical renewal, culminating in the acclaimed album, Dance Hall Style, for Bronx-based producer Lloyd ‘Bullwackie’ Barnes in 1982, which referenced reggae’s latest dance incarnation. “It was a different sound at his studio, and I would say Wackies was the Studio One of New York,” Horace emphasises. “Every artist goes there because he gives everybody a break.”

To avoid any chance of stagnating, Horace then shifted base to London, where his innovative 1985 album, Elementary, shook up the reggae scene.

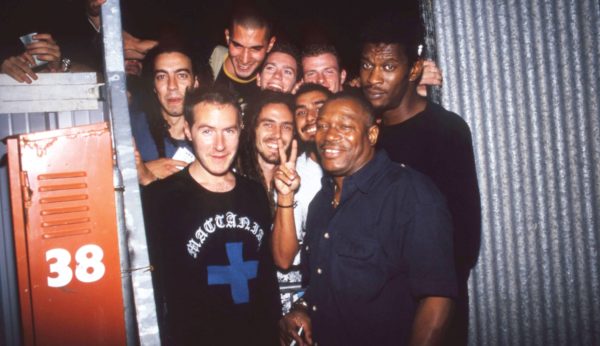

Released by indie giant Rough Trade and created with keyboardist Caroline Williams of Akabu, along with two founding members of Aswad, it helped pave the way for an approach from Massive Attack during the recording of their ground-breaking debut album, Blue Lines, in 1991.

“I was Daddy G’s favourite reggae singer, which I never even knew,” Horace laughs. “They sent a cassette and me and Caroline sit down and wrote the track ‘One Love’, so that’s where we really started, and meeting Massive felt like a U-turn, because I was already trying to do songs like those on Elementary. So when I met Massive, I really wanted to do that kind of music.”

These days, when not on tour, Horace spends most of his time in Kingston, where he and his son run a recording studio, Higher Grades, helping to nurture emerging talent. Last November, when lockdown restrictions were in full force, Horace’s dynamic performance was a highlight of the livestreamed No Bass Like Home, celebrating the designation of Brent as the London Borough of Culture. (Historically Brent has been an area that helped to establish reggae in Britain; Trojan Records was based there in the Sixties and Seventies.)

Horace insists that his enduring positivity results from his faith in Rastafari, and his continual immersion in music. “I still have about four or five LPs for myself that have never ever been released, so I’ll probably release them in the future, if life spares me,” he says, with another chuckle.

“Anywhere I go in the world, Jah carries me through. From when I was eighteen years old, I’m a Rastafarian, and if you’re living conscious, you must think conscious things, but if you’re doing evil, of course you’re going to stick to evil things. I start to learn about consciousness from a young age, and it’s been good for me.”

The Music That Defined Me: Carroll Thompson

9 October 2024

The singer names the albums by British singers and bands that inspired and influenced her career

WHAT'S ON

Discover what's going on across our famous venues

Boisdale Grand Cru Tasting Bordeaux v Chile

Belgravia

10 March 2026

An exclusive event for Boisdale members and guests with Viña Santa Rita, voted the world’s number one winery by Forbes. Enjoy a seated, tutored Grand Cru blind tasting at Boisdale of Belgravia as Chilean fine wines including Casa Real are tasted against classified growth Bordeaux. Six wines and five canapés per guest.

Frank Sinatra & Friends

Canary Wharf

11 March 2026

Stephen Triffitt, praised by Frank Sinatra Jr. as “the best, the greatest”, joins West End star Mark Adams as Dean Martin and acclaimed jazz singer Nicola Emmanuelle as Ella Fitzgerald for an evening of swing classics including “Fly Me to the Moon”, “That's Amore” and “The Lady Is a Tramp”

Negroni Masterclass

Belgravia

18 March 2026

Join us for an intimate Negroni Masterclass with Bar Manager Brian Calleja at Boisdale of Belgravia. Begin with a welcome Americano before exploring Italy’s aperitivo culture and the story behind the classic Negroni in the elegant Negroni Bar.

Legend: The Music of Bob Marley & The Wailers

Canary Wharf

21 March 2026

Experience the spirit of Bob Marley with LEGEND, the UK’s leading Marley show. Fronted by Michael Anton Phillips and his all-star band, expect timeless reggae anthems from “No Woman, No Cry” to “Is This Love” in a night of pure One Love at Boisdale.

The Ultimate Elton John Show

Canary Wharf

25 March 2026

Max Anthony brings his acclaimed celebration of Elton John to Boisdale of Canary Wharf for the first time. Expect piano-driven classics including Rocket Man, Tiny Dancer and I’m Still Standing, performed with flair by a superb live band in Boisdale’s signature setting of fine food, cocktails and late-night atmosphere.

Brit Funk Association

Canary Wharf

9 April 2026

Featuring key members from iconic bands like Light of the World, Hi-Tension, and Beggar & Co, this collective of legends delivers the sound of Brit Funk from the late 70s and 80s.