Saddam: My Part In His Downfall

Thirty years-ago, a US-led coalition kicked the Iraqi Army out of Kuwait. General Sir Simon Mayall tells Michael Karam about the war he very nearly missed

By Michael Karam

February 14 2023

Simon Mayall opens the door to his West London flat with a hearty “Come in, come in.” No pandemic elbow-bumping here, just a solid handshake. “Coffee?” Mayall disappears to rummage in the kitchen. The high-ceilinged sitting room is stuffed with books and souvenirs from a life of adventure and travel. “Nice place you’ve got,” I venture. “Thank you,” Mayall says, emerging with two mugs. “It’s what I call my Richard Hannay bachelor pad.”

John Buchan’s Edwardian literary hero wouldn’t mind the comparison. Last year, Mayall – or to give him his full title, Lieutenant General Sir Simon Vincent Mayall KBE, CB – published his memoir, Soldier in the Sand: A Personal History of the Modern Middle East, to positive reviews, and has had what can only be described as a Boy’s Own life.

From the radio in the kitchen, news from Kabul drifts in. Mayall shakes his head. “This is an avoidable and unnecessary debacle. For very little blood, and not much treasure, we were helping sustain so many hard-won gains. The Romans understood the requirement for ‘strategic patience’ when striving to defend your civilisation and your citizens.”

The son of an RAF officer, Mayall grew up in Yemen and Malaysia at a time when Britain was shedding the last of its imperial skin. He joined the Army in 1979, was commissioned into a glamorous cavalry regiment, and then came a fortuitous three-year secondment to the Sultan of Oman’s Armed Forces (SAF). This experience not only established his bona fides as a desert soldier and helped shape a glittering career, but also inspired an enduring fascination and love for the Middle East, proving that timing is everything: The two decades between 1990 and 2010 offered rich operational pickings denied to the previous generation of soldiers, especially cavalrymen, who sat on the Rhine waiting for World War III. But then came the Gulf War of 1991, the Kosovo War in 1999, the Iraq War in 2003, and the War in Afghanistan. It was the Gulf War, fought and won at lightning speed 30 years ago, that we have met to discuss.

“Until then, the most action any British soldier eager to be blooded by conflict could hope for was in Northern Ireland, more a police action than conventional soldiering,” Mayall recalls. “Only the 1982 Falklands conflict offered the opportunity to do what we had trained for and, I admit, many of those who didn’t go felt they had missed out.

“It might sound unfashionable to say so, but if you are a youngish officer full of martial ardour, you rather feel you want your war. When Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi Army invaded Kuwait in August 1990, I was working at the MOD! I was tearing my hair out. I had commanded armour in the desert with the SAF and I spoke Arabic. I felt I should be there.”

To make matters worse, his regiment at the time – the 15th/ 19th Hussars – wasn’t earmarked to go either. It was only in October, at the annual SAF dinner in London, that, over cigars and brandy, Mayall chanced his hand and pled his case to the late Lt General Sir Johnnie Watts.

“Watts happened to be great mates with Commander-in-Chief of the British Forces, General Sir Peter de la Billière, and promised he’d look into it,” Mayall says. “He asked me to scribble my name down on a scrap of paper that he stuffed into his dinner jacket. ‘My wife Di always goes through my pockets the next day so she’ll make sure I won’t forget,’ he assured me. I was encouraged but, given the lateness of the hour, not convinced.”

On such things the direction of one’s life can hang. But Lady Watts found the paper and, although it took a few weeks, Mayall did receive his orders to report to Major General Rupert Smith’s staff in Saudi Arabia. “My boss at the MOD thought it highly irregular, but he couldn’t really argue. Johnnie Watts had told Peter de la Billière that he ‘couldn’t win the war without me’, which of course was absolute nonsense, but I wasn’t going to argue.”

Mayall was one of General Smith’s Ops officers, coordinating 7 and 4 Brigades, Engineers and Artillery as well as liaising with the US 7 Corps. And so, with nothing much in the way of suitable kit except an Asprey’s cigarette case given to him by a girlfriend “to stop a bullet”, Mayall headed to the Arabian Peninsula, his enthusiasm to be “part of history” only slightly tempered by the alarmingly high estimates of coalition casualties.

“My initial enthusiasm to get stuck-in had waned slightly,” Mayall admits.

“Even though I wasn’t leading the charge in a tank, chemical weapons were the big fear and we all certainly thought it was going to be more of a slugging match.” In the end it was a relative cake walk.

The British 1st Armoured Division played a decisive role in the “Left Hook” – an action that destroyed more than 300 Iraqi armoured vehicles. Tank commanders raced across the desert expecting at any minute to hit stubborn opposition, but it wasn’t to be.

“We thought the Republican Guard would stand and fight but they didn’t, and in the end, despite the media hype that we were going up against a huge, battle hardened army, the simple truth was that Saddam Hussein’s forces were just no match for the well-drilled armies of the US and the UK. It simply boiled down to quality,” explains Mayall, who admits to having huge respect for the US Armed Forces after going on to work with them in Kosovo, Iraq and Afghanistan.

Mayall is also convinced that the coalition’s failure to “tie things off” enabled Saddam’s army to fight another day (and to crush the Kurdish and Shia uprisings), and allowed him to write a parallel narrative in which he portrayed himself as the victor to his supporters across the Arab world. This soured an outstanding feat of arms. “We should have left him in no doubt that he’d been beaten,” Mayall says. “We should have dragged him to the peace table in front of the world’s cameras. It would’ve saved more lives and suffering in the long run. Maggie [Thatcher] would’ve finished the job. I asked her as much at a dinner in 2007, and she agreed, but [by February 1991] she’d been ousted by her own party.”

Mayall retired from soldiering in 2015, but his world view continues to evolve, especially regarding the turbulent Middle East, whose layered complexities demand an astute and nuanced understanding of the area and its people. It is a recurring theme in his book. “The Middle East is ethnically, culturally, religiously, and even linguistically diverse. So much so, that it’s absurd to simply lump everyone together as Arabs. And that, to me, is the enduring fascination of the region.”

Simon Mayall’s Soldier in the Sand: A Personal History of the Modern Middle East is published by Pen & Sword

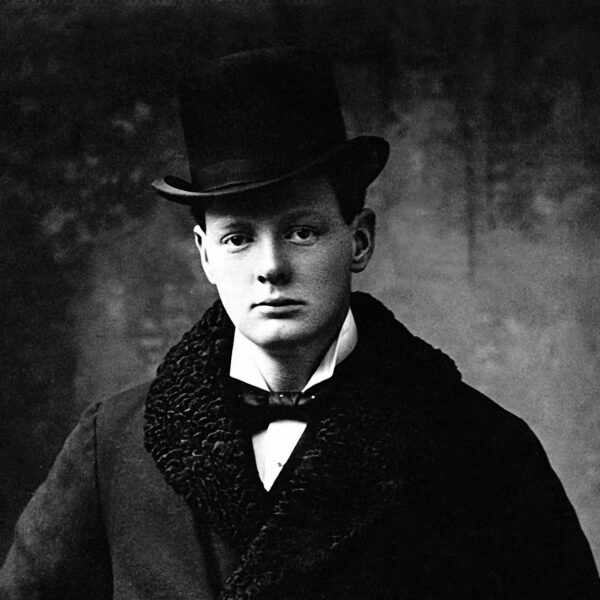

Winston Churchill: Destiny’s Child

8 October 2024

Despite his share of failures, Bruce Anderson reminds us that the stars aligned to ensure the wartime leader's legacy of greatness

WHATS' ON

Discover what's going on across our famous venues

Boisdale Grand Cru Tasting Bordeaux v Chile

Belgravia

10 March 2026

An exclusive event for Boisdale members and guests with Viña Santa Rita, voted the world’s number one winery by Forbes. Enjoy a seated, tutored Grand Cru blind tasting at Boisdale of Belgravia as Chilean fine wines including Casa Real are tasted against classified growth Bordeaux. Six wines and five canapés per guest.

Frank Sinatra & Friends

Canary Wharf

11 March 2026

Stephen Triffitt, praised by Frank Sinatra Jr. as “the best, the greatest”, joins West End star Mark Adams as Dean Martin and acclaimed jazz singer Nicola Emmanuelle as Ella Fitzgerald for an evening of swing classics including “Fly Me to the Moon”, “That's Amore” and “The Lady Is a Tramp”

Negroni Masterclass

Belgravia

18 March 2026

Join us for an intimate Negroni Masterclass with Bar Manager Brian Calleja at Boisdale of Belgravia. Begin with a welcome Americano before exploring Italy’s aperitivo culture and the story behind the classic Negroni in the elegant Negroni Bar.

Legend: The Music of Bob Marley & The Wailers

Canary Wharf

21 March 2026

Experience the spirit of Bob Marley with LEGEND, the UK’s leading Marley show. Fronted by Michael Anton Phillips and his all-star band, expect timeless reggae anthems from “No Woman, No Cry” to “Is This Love” in a night of pure One Love at Boisdale.

The Ultimate Elton John Show

Canary Wharf

25 March 2026

Max Anthony brings his acclaimed celebration of Elton John to Boisdale of Canary Wharf for the first time. Expect piano-driven classics including Rocket Man, Tiny Dancer and I’m Still Standing, performed with flair by a superb live band in Boisdale’s signature setting of fine food, cocktails and late-night atmosphere.

Brit Funk Association

Canary Wharf

9 April 2026

Featuring key members from iconic bands like Light of the World, Hi-Tension, and Beggar & Co, this collective of legends delivers the sound of Brit Funk from the late 70s and 80s.