The Great British Picnic

Tom Parker Bowles examines why we are obsessed with such an inconvenient, counterintuitive dining ritual

By Tom Parker Bowles

July 4 2023

Two lines of typical Betjeman brilliance, “Sand in the sandwiches, wasps in the tea”, from his poem, Trebetherick, pithily distil the British obsession with picnics. Our relationship with this particular al fresco feast is complicated, to say the least. A triumph of hope over experience, a naïve fantasy that invariably ends in tears. How many times have we set off, with a spring in our step and a tune on our lips, before settling into some bucolic spot, blanket unrolled and booze uncorked, only for the skies to darken, the thunder to rumble and the downpour to begin? Which means the picnic ends, as usual, with everyone crammed in the car, the air thick with the sickly pong of cheap pork and despair, listening to the desolate pitter patter of rain on the roof.

Equally gloomy is the typical British picnic spread. A pair of neon-hued Scotch eggs, softly sinister, bad breath in ovoid form. And chewy, wrinkled chipolatas, speckled with hard nubbins of gristle, that resemble Napoleon’s pickled cock. Sandwiches, sullen and sad, some stuffed with a fistful of sweaty, pre-grated industrial cheddar. Others sullied with soggy flaps of ham. All are smeared with an excess of margarine. There are chicken legs, with their scrotum-like skin, tasting of nothing, save a short, miserable life. And supermarket quiche with the consistency of wet cardboard, tainted with a whiff of stale vomit, the very definition of dyspeptic depression. Impotent sticks of celery, tasteless tomatoes and boiled eggs. Always boiled bloody eggs, cooked to buggery. Strawberries, fat and pouting but utterly devoid of taste, round off this sorry affair. When the only highpoint is a half-melted Wagon Wheel, you know that this is a lunch fit only for the third circle of Dante’s Inferno.

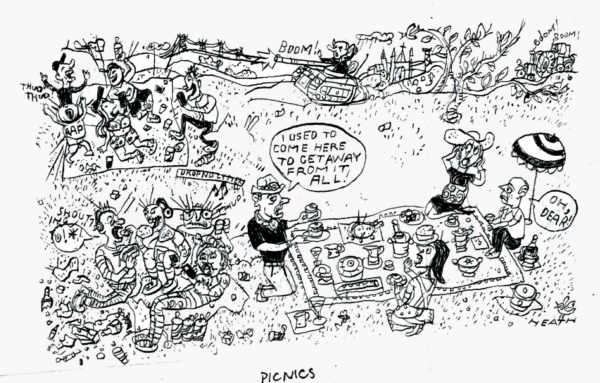

To make things even worse, this sorry dirge is usually endured while under attack from kamikaze wasps, marauding ants, and irate farmers. For those hankering after a more urban experience, there’s always the local park. Where rubbish music dribbles through tinny speakers, muscular Staffies roam wild, and there’s more dog shit than grass. Oh, and your rus in urbe Arcadia is enveloped in an all-encompassing fug of skunk. Seriously, why the hell do we bother?

I get that eating outdoors, in Britain, on a fine day, is a rare pleasure. Cold rosé and cool shade. But that’s the point. Shade. Always shade. Because who wants to sit in the full glare of the midday sun, skin turning a vicious pink, sweat coursing down one’s brow? Certainly, no one who actually lives in a hot country. The French, Italians, and Spanish look at us as if we’re lunatics. Mad dogs and Englishman and all that. And yes, I know that history, art, and literature are filled with splendid picnics. Those vast colonial affairs up in Shimla, the summer capital of the Raj, where battalion of liveried staff (always Indian, obviously) scuttled about with platters of mutton chops, tinned asparagus, and potted snipe. Then there’s Le Déjeuner Sur l’Herbe, a lunch rather enlivened by a lady entirely unencumbered by clothes. Probably some decent white Burgundy, too. Although Emma’s Box Hill expedition (in Austen’s classic) sounded like a right bore.

And yes, I also know that an article about picnics is never complete without at least passing reference to The Wind in the Willows and Ratty’s wicker basket: “There’s cold chicken inside it,” replied the Rat briefly: “coldtonguecoldhamcoldbeefpickled gherkinssalad frenchrollscresssandwichespotted meatgingerbeerlemonadesodawater–” Credit where credit’s due, though. The rodent really knows his tucker. But in the interest of stating the bleeding obvious, these are animals. Who talk. And wear clothes. In a children’s book. So perhaps not the best evidence for the glories of the English picnic, M’lord.

But enough of doom and gloom. A picnic can be a very fine thing indeed. It has its roots in Medieval hunting feasts (the word comes from the French, pique-nique), in which hungry kings and hangers-on devoured baked meat, hams, and mead to get them in the mood for the chase. Before ending the day cooking up the more perishable parts of the deer (or ‘umbles). And while picnics may seem a uniquely British thing, the Japanese are masters of the art, thronging, during cherry blossom season, to eat beneath those fragrant flowers. While the Chinese feast at the graves of their relatives, offering choice morsels to those in the sweet hereafter.

So what makes a decent picnic? The company, of course. Far rather a Boot’s Meal Deal for two with good mates, than a kilo of caviar with bores. And booze, rosé and white, stored in the fridge for a few days before. Then transplanted into cool boxes, with a ton of ice – and ice is key. Utterly essential. Fill another cool box with the stuff. Do not forget your corkscrew. Or a sharp knife. As to the food, keep it simple. York ham, carved thick and served with fresh, crusty bread, and a fat blob of English mustard. Pata negra, sliced thin, along with culatello, bresaola, and coppa. Potted shrimps, dressed crab, and smoked salmon; decent tinned anchovies (Ortiz never let you down), piled high on lavishly buttered bread; some of Mitch Tonk’s magnificent Rockfish canned mackerel, and maybe, if you’re feeling particularly extravagant, a couple of steamed lobsters. Served with lemon and Helman’s mayonnaise. Pan bagnat is another classic, made the day before, so all that anchovy- and tuna-infused oil soaks into the bread.

A fillet of beef will never go amiss, cooked pink, and lavished with horseradish. And perhaps a vittello tonnato, heavy on the tuna, and a decent Niçoise, heavy on the anchovies. Whole roast chicken, ready to be torn apart and stuffed into baps with more mayonnaise. Pork pie, a proper one, all firm flesh, wobbling jelly and flaky pastry. Or a pâté en croute. Always a pâté en croute.

Eggs, in any form (save boiled to death) are tip-top picnic food. My father talks longingly of Plover’s – the best, he says, of them all. They’re now illegal, although who can forget Sebastian Flyte’s immortal words: “Mummy sends them from Brideshead. They always lay early for her.” Gull’s eggs are equally magnificent, although it’s been a couple of years since I last had a taste. Peas, too, and broad beans, in the pod, with a small pile of Maldon salt. As well as tomatoes warmed by the sun, and at their peak of sweetness, anointed with olive oil and salt.

For pudding, keep it simple. English cherries, Scottish raspberries, clotted cream. A lemon tart, if you’re feeling inspired. And cheese, good cheese, a proper West Country Cheddar, from Keen’s, Quicke’s, or Montgomery’s. Ripe brie or Stinking Bishop too. (Wrap them up tight, and put in a sealed box, unless you want to car to smell like a Cairo morgue in mid-summer. When the air conditioning’s just gone caput.) Something light and goaty if you must. God, I’m getting hungry just writing this. And I now realise I do rather adore picnics. But I still don’t feel any urge to strike off for the sunlit uplands. No, this picnic will taste every bit as sweet in my garden, in the shade, mere metres from the back door. And when the inevitable rain appears, we can just slip inside and merrily carry on. So blow winds and crack your cheeks. Rage! Blow! Because this is one picnic that even a tempest cannot destroy