Money and Maharajas

A rollicking read and cautionary tale, William Dalrymple’s new book tells the story of the mighty East India Company, and how it took control of one of the world’s most magnificent empires

By William Dalrymple

December 20 2019

How did the Moghul Empire, a vast expanse of princely states forming what we now know as India, become dominated by “a dangerously unregulated private company, based thousands of miles overseas and answerable only to its shareholders”?

In The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company (Bloomsbury), William Dalrymple charts the primacy of this privately-armed trading behemoth, which helped forge Britain’s colonial ambitions. In this edited extract, salty sea dogs try to charm the Moghul Emperor, Jahangir.

It is always a mistake to read history backwards. We know that the East India Company (EIC) eventually grew to control almost half the world’s trade and become the most powerful corporation in history, as Edmund Burke famously put it, “a state in the guise of a merchant”. In retrospect, the rise of the Company seems almost inevitable. But that was not how it looked in 1599, for at its founding few enterprises could have seemed less sure of success.

At that time England was a relatively impoverished, largely agricultural country, which had spent almost a century at war with itself over the most divisive subject of the time: religion. In the course of this, in what seemed to many of its wisest minds an act of wilful self-harm, the English had unilaterally cut themselves off from the most powerful institution in Europe, so turning themselves in the eyes of many Europeans into something of a pariah nation. As a result, isolated from their baffled neighbours, the English were forced to scour the globe for new markets and commercial openings further afield. This they did with a piratical enthusiasm.

On 28 August 1608, Captain William Hawkins, a bluff sea captain with the Third Voyage, anchored his ship, the Hector, off Surat, and so became the first commander of an EIC vessel to set foot on Indian soil.

India then had a population of 150 million (about a fifth of the world’s total) and was producing about a quarter of global manufacturing; indeed, in many ways it was the world’s industrial powerhouse and the world’s leader in manufactured textiles. Not for nothing are so many English words connected with weaving – chintz, calico, shawl, pyjamas, khaki, dungarees, cummerbund, taffetas – of Indian origin.

It was certainly responsible for a much larger share of world trade than any comparable zone and the weight of its economic power even reached Mexico, whose textile manufacture suffered a crisis of ‘deindustrialisation’ due to Indian cloth imports.

In comparison, England then had just five per cent of India’s population and was producing just under three per cent of the world’s manufactured goods.

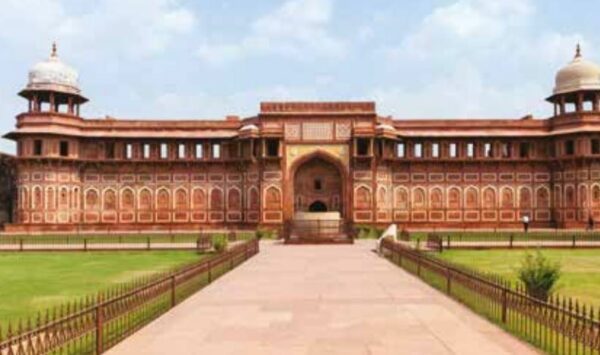

A good proportion of the profits on this found its way to the Mughal exchequer in Agra, making the Mughal Emperor, with an income of around £100 million, by far the richest monarch in the world.

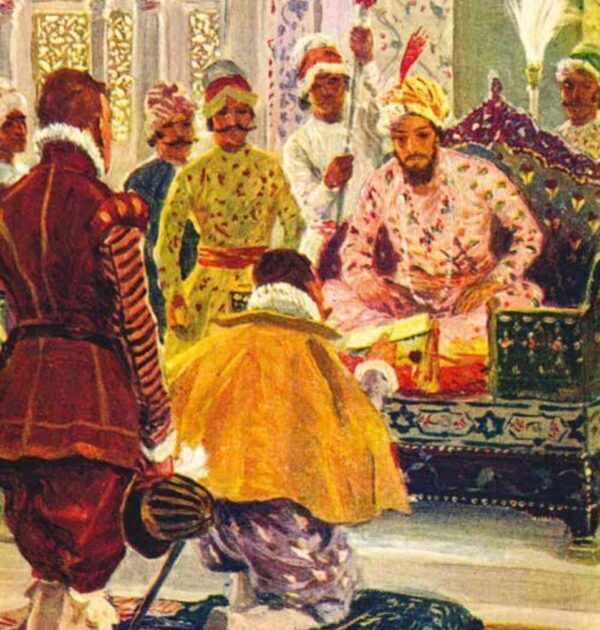

The Company realised that if it was to trade successfully with the Mughals, it would need both partners and permissions, which meant establishing a relationship with the Mughal Emperor himself. It took Hawkins a year to reach Agra, which he managed to do dressed as an Afghan nobleman.

Here he was briefly entertained by the Emperor Jahangir, with whom he conversed in Turkish, before Jahangir lost interest in the semi-educated sea dog and sent him back home with the gift of an Armenian Christian wife.

A new, more impressive mission was called for, and this time the Company persuaded King James to send a royal envoy. The man chosen was a courtier, MP, diplomat, Amazon explorer, Ambassador to the Sublime Porte and self-described “man of quality”, Sir Thomas Roe.

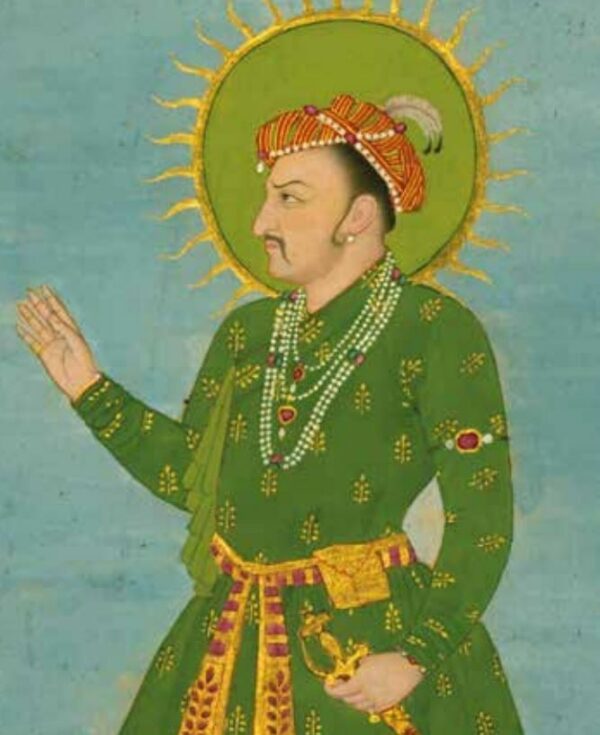

In 1615 Roe finally arrived in Ajmer, bringing presents of “hunting dogges” – English mastiffs and Irish greyhounds – an English state coach, some Mannerist paintings, an English virginal and many crates of red wine for which he had heard Jahangir had a fondness. Roe nevertheless had a series of difficult interviews with the Emperor. When he was finally granted an audience, and had made his obeisance, Roe wanted immediately to get to the point and raise the subject of trade and preferential customs duties, but the aesthete Emperor could barely conceal his boredom at such conversations. Jahangir was a proud inheritor of the Indo-Mughal tradition of aesthetics and knowledge. As well as maintaining the Empire and commissioning great works of art, he took an active interest in goat and cheetah breeding, medicine and astronomy, and had an insatiable appetite for animal husbandry, like some Enlightenment landowner of a later generation.

Roe would try to steer the talk towards commerce and diplomacy and the “firmans“ (imperial orders) he wanted confirming “his favour for an English factory” at Surat and “to establish a firm and secure Trade and residence for my countrymen” in “constant love and pease”; but Jahangir would assure him such workaday matters could wait, and instead counter with questions about the distant, foggy island Roe came from, the strange things that went on there, and the art which it produced.

“He asked me what Present we would bring him,” Roe noted. “I answered the league [between England and Mughal India] was yet new, and very weake: that many curiosities were to be found in our Countrey of rare price and estimation, which the king would send, and the merchants seeke out in all parts of the world, if they were once made secure of a quiet trade and protection on honourable Conditions. He asked what those curiosities were

I mentioned, whether I meant jewels and rich stones. I answered No: that we did not thinke them fit Presents to send backe, which were first brought from these parts, whereof he was the Chiefe Lord … but that we sought to find things for his Majestie, as were rare here, and vnseene. He said it was very well: but that he desired an English horse … So with many passages of jests, mirth, and bragges concerning the Arts of his Countrey, he fell to ask me questions, how often I drank a day, and how much, and what? What in England? What beere was? How made? And whether I could make it here. In all which I satisfied his great demands of State.”

Roe could on occasion be dismissively critical of Mughal rule – “religions infinite, laws none” – but he was, despite himself, thoroughly dazzled. In a letter describing the Emperor’s birthday celebrations in 1616, written from the beautiful, hilltop fortress of Mandu in central India to the future King Charles I in Whitehall, Roe reported that he had entered a world of almost unimaginable splendour.

When Roe eventually returned to England, after three weary years at court, he had obtained permission from Jahangir to build a factory (trading station) in Surat, an agreement “for our reception and continuation in his domynyons” and a couple of imperial firmans, limited in scope and content, but useful to flash at obstructive Mughal officials.

Jahangir, however, made a deliberate point of not conceding any major trading privileges, possibly regarding it as beneath his dignity to do so. Yet for all its clumsiness, Roe’s mission was the start of a Mughal–EIC relationship that would develop into something approaching a partnership and see the company gradually drawn into the Mughal nexus.

Over the next 200 years it would learn to operate skilfully within the Mughal system and to do so in the Mughal idiom, with its officials learning good Persian, the correct court etiquette, the art of bribing the right officials and, in time, outmanoeuvring all their rivals – Portuguese, Dutch and French – for imperial favour. Indeed, much of the Company’s success at this period was facilitated by its scrupulous regard for Mughal authority. Before long, indeed, the Company would begin portraying itself to the Mughals, as the historian Sanjay Subrahmanyam has nicely described it, as “not a corporate entity but instead an anthropomorphised one, an Indo-Persian creature called Kampani Bahadur”.

By kind permission of Bloomsbury Publishing.