Nasser's Henchmen

The amazing story of the former Nazis who helped Egypt build a modern state after World War II

By Michael Karam

July 5 2023

One day in February 1950, Europe’s most wanted man, was spotted blithely drinking a glass of pastis in a Paris café in the company of an attractive woman. He was SS Obersturmbannführer Otto Skorzeny, holder of the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves; darling of the German Special Forces in the Second World; hero of the 1943 Gran Sasso raid to rescue Mussolini was, at the time, running an escape network - codenamed The Spider - for former Nazis seeking to ‘relocate’ from Europe.

He wore many hats. He was military adviser and arms dealer to the Egyptian government, and as such, a key player in one of the most intriguing, and often sinister, episodes in the immediate post-war era and the history of the modern Middle East.

Skorzeny and his cohort of ex-Nazis were still smarting from defeat in the costliest war humanity had known and were eager to remind the world that they had unique, and often unfulfilled skill sets, ones that would be attractive to any gung-ho regime with aspirations to be a major player in a brave new world and happy to use their unique talents.

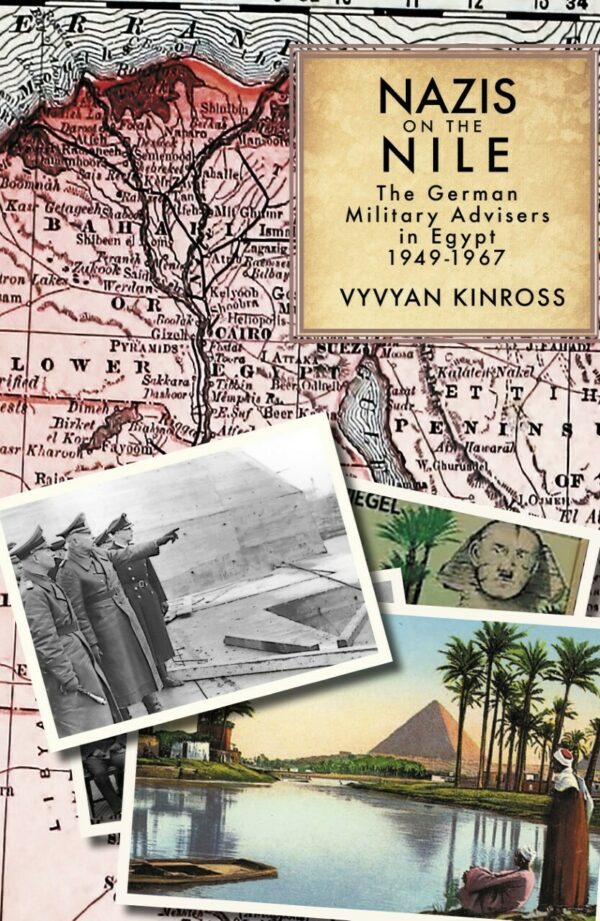

In his latest book, Nazis on the Nile, published last year, Vyvyan Kinross has told the story of what happened to these former Wehrmacht professionals, as well as the scientists and engineers, who helped, first King Farouk, and then President Gamal Abdel Nasser, create a new Egyptian state between 1949 and the Six-Day War in 1967. They would assist Egypt in building a modern military industrial complex in a bid to make it the pre-eminent force in the post-colonial Middle East and in the process generate genuine concern among those involved in the struggle for dominance in the region.

By the end of the Second World War, Egypt was the richest country in the Middle East, but its wealth, mostly generated from its huge cotton industry, lived side-by-side with extreme poverty. King Farouk was viewed by his people as an extravagant and corrupt halfwit, who was responsible by his people for Egypt’s defeat in the 1948 war with Israel and the failure to prevent the subsequent creation of the Jewish state.

The tubby monarch had a penchant for high-end porn, fast cars, gilded furniture and equally ornate women, but he also had a vision for a new Egypt. Before he was forced into exile in July 1952 after being overthrown in a military coup initiated by the so-called Free Officers Movement, which included Nasser, he had begun putting out feelers to former Nazis.

Farouk wanted Egypt to become a regional superpower. He wanted better weaponry and military hardware, in particular he sought out the brains to design, develop and produce Egypt’s first jet engine fighters and missiles. As Kinross explains, “his vision was an Egypt with a clenched fist, its confidence bolstered by the crunch of well-drilled military boots on the ground; Egyptian fighter jets in the skies above Cairo, its warship steaming across the eastern Mediterranean and state of the art missiles pointing skywards reaching for the hearts of its enemies”.

All this wasn’t lost on Egypt’s new military leaders, who also had plans of their own. Over the next 15 years, Nasser would also rely on German freelancers to add muscle to his vision of Arab Nationalism.

But they weren’t just technicians and soldiers. There were also state security experts, bankers and propagandists. All had a role, sometimes very dark and uncomfortable roles, to play in the new Egypt.

The dramatis personae of this story is particularly long and colourful and include many of Nazi Germany’s more unsavoury characters – even the notorious Adolf Eichmann has a walk on role before being abducted by the Israelis in Argentina – all of whom were, at least initially, happy to seek sanctuary in Egypt. Many even adopted Arab noms de guerre and converted to Islam.

As well as Skorzeny, they included Artur Schmitt, the former Afrikakorps commander who would become an adviser to King Farouk and the Arab League. There was former SS officer Dr Wilhelm Voss who would become a key player in Egypt’s Central Planning Board and who was instrumental in much of the hiring, in particular the recruitment of the rocket scientists including the fanatical ex-SS officer Dr Rolf Engel, the former wartime head of Skoda research centre in the then Czechoslovakia, who became head of head of Egypt’s rocket program.

We also have the propaganda guru Dr Johann “Omar Amin” von Leers, a former SS Sturmbannführer and head of anti-Semitic propaganda at the sinisterly-named Ministry of National Guidance.

Not surprisingly, it was a dark period for Egypt’s 50,000 Jews who would have to ‘pay a price for Israel’s alliances and military choices’. Indeed, after the ill-fated Suez campaign, Egypt’s Jews realised there was no future. Thousands left either for Europe or Israel in an atmosphere of expulsions, internments, confiscation of properties and a change to the nationality laws. Sound familiar?

One of the main architects of this shameful initiative was Leopold Gleim, a former SS officer, who had been in charge of Jewish affairs in Poland during WW2. Gleim arrived in Egypt in the mid-50s, renamed himself Ali Al-Nashar and converted to Islam. He then enrolled as an employee of the Ministry of the Interior with responsibility for, yes you guessed it, Jewish affairs.

But surely the most disturbing charge levelled at Nasser’s regime was the establishment of internment camps for hundreds jews, communists, trade unionists and other dissidents. Comparisons with Nazi Germany’s Final Solution could not have been more obvious but, as Kinross explains, it ‘stopped far short of any kind of extermination strategy, systematic or otherwise’. It did however represent the darkest side of German ‘expertise’ and prompted British Prime Minister Anthony Eden to call Nasser ‘Hitler of the Nile’.

Defeat for Egypt in the Six-Day War heralded the winding down of German involvement in Egyptian affairs. The army had been defeated for the third time in 20 years and Nasser’s ambitions for Egypt to attain regional superpower status had been dealt a fatal blow.

One of the problems was that the Germans felt muzzled, unable to give full expression to their considerable ‘talents’. There was a famous stand-up row between Nasser and Generalmajor Oskar Munzel’s, a headstrong former Panzer commander who slammed his fist on the president’s desk, criticising the Egyptian refusal to allow German executive authority and battlefield command. ‘What was missing was German leadership and decision-making at the sharp end of tactical deployment and combat itself,” says Kinross. “To this extent, the engagement of German experts and their advice without the propulsion or authority of official German foreign policy behind it was bound to fail at a strategic level.”

The Egyptians missed a trick. It is highly likely that if German officers had been allowed battlefield command, the performance of Egyptian troops during Suez would have been more robust and while they may not have defeated the tripartite alliance of Britain, France and Israel, Egypt’s military stock would have undoubtedly risen. It begs wondering what another ten years of German leadership would have done to the quality of Egyptian soldering.

But the high-functioning Germans simply couldn’t cope with a state with aspirations beyond its means and which was burdened by an antediluvian and woefully inefficient bureaucracy, and a life often dogged by heat, disease and the ever-present fear of Israeli hit squads.

Nasser died in 1970. His funeral, attended by an estimated 5 million people, was one of the biggest public events in history. Three years later, in the 1973 Yom Kippur War with Israel, Egypt once again found itself on the losing side. Today’s Egypt has the tenth biggest army in the world. As an institution, it is, according to Kinross, “self-assured and autonomous, deeply embedded in the country’s economy and a major recipient of foreign military aid”. Add to this a security system that employs over 400,000 personnel, and it is easy to see how these apparatuses of state wield huge power that trumps every other national institution.

In a way, Nasser and his fellow Free Officers got what they wanted after all.